With more than 500,000 registered nurses (RN) retiring by 2022, the United States Bureau of Labor Statistics projected the need for 1.1 million new RNs for expansion and replacement of retirees, and to avoid a nursing shortage.

Given these statistics, UW Health is focused on removing any barriers to recruitment. We started an Ambulatory Nurse Residency Program in winter 2020-2021 aimed at helping new nurses transition to their first professional nursing job.

UW Health has 84 clinics and more than 3 million outpatient clinic visits per year, providing nurses with diverse experiences, says Terri White, nursing education specialist and Nurse Residency Program coordinator for our ambulatory clinics.

“There is this notion that new nurses have to work in a hospital setting and take care of sick patients in a hospital, that you can’t work in a clinic setting until later in your career,” Terri says. “But clinic nursing has opportunity for extensive growth. Clinic nurses are critical to the healthcare team, and we are here to give them the training they need to succeed in this demanding and important profession.”

Since burnout is a key contributor to nurses leaving the field early in their careers, UW Health has created a 12-month program to help ensure new nurses are well-trained and become acclimated to stay in the nursing field.

Our ambulatory program began in February 2021. The residency is for new nurses who just finished nursing school, and places them in a clinic setting (ambulatory) with a mentor (preceptor) to learn the job in a real-world setting. Additionally, the nurses take two nursing classes per month, with frequent check-ins and evaluations by program coordinators. The program runs two groups per year and expects to expand their numbers.

“I am so glad the Ambulatory Nurse Residency exists to get nurses into the ambulatory world,” says Kaarina Powell, BSN, RN, current ambulatory nurse resident. “I hope this program continues to grow and provide opportunities for other nurses like me, to help patients in the clinic setting.”

UW Health has been running an inpatient Nurse Residency Program since 2004 that helps new nurses adjust during their first year taking care of patients in hospitals. Since that program began, the first-year retention rate for nurses at UW Health has been (on average) 97 percent. The national average for programs with a nurse residency program is 91 percent. For hospitals that do not have nurse residency programs, the retention rate is 71 percent.

Terri says, “By keeping nurses in the field through a program like ours, we can do our part to address this looming nurse shortage.”

ORs partner with local nursing school

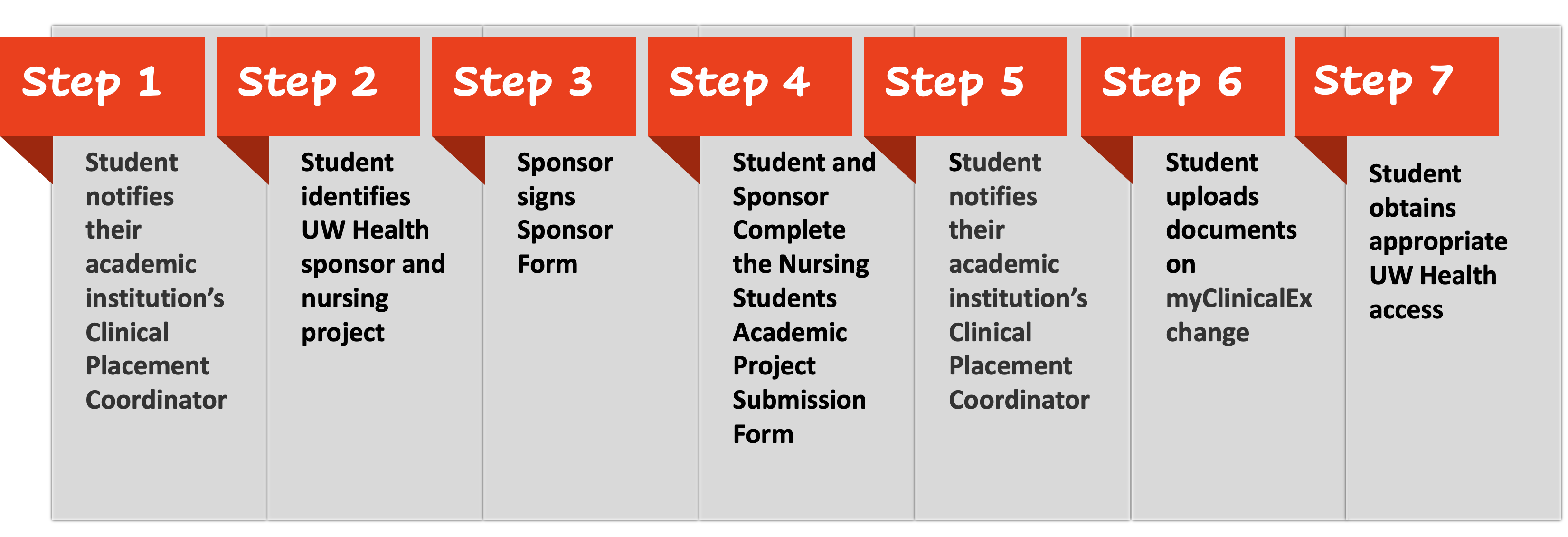

Starting in fall 2021 the UW Health Peri-Operative Departments at American Family Children’s Hospital, The American Center and Madison Surgery Center partnered with the local Edgewood College Nursing program to provide clinical sites for nursing students who were interested in learning more about perioperative nursing.

“These nursing students were provided many hours of didactic and skills/lab-based training prior to starting their clinicals, to ensure they had a solid foundation of the core role and skills needed to function in a perioperative department,” states Tricia Ejzak, MSN, RN, CNOR, Nursing Education Specialist. “Their clinical time was spent with RNs but also included time observing in the many departments of the hospital that provide daily support to the OR, such as Reprocessing, Anesthesia, and Medical Imaging.”

Students were able to observe the surgical experience for our patients from admission to discharge. “This program will help UW Health attract new graduates to perioperative nursing jobs and prepare them to be able to successfully transition into their new role,” states Laura Ahola, MSN, RN, Director of Surgical Services, American Family Children’s Hospital. “It will also increase retention of these new clinicians and prepare them for the opportunity to become a Certified Nurse of the Operating Room (CNOR).”

The success of the program has built tremendous excitement across UW Health, knowing that the number of clinical site opportunities will be increasing within the organization.

New role to support clinical staff

Given the growing concerns about workforce challenges pertaining to filling licensed/certified clinical roles, a UW Health workgroup began meeting and identified an improvement opportunity to use the framework designed for the RN Helper role (used during the first COVID surge), to create the Nursing Care Partner (NCP) position. The NCP role has been designed to provide support to inpatient staff with tasks that are often time consuming or do not require a clinical background, thereby allowing clinical staff to focus on the care their patients need. The NCP position provides an opportunity for those who are interested in healthcare, but not yet clinically trained, to support our patients and staff in the inpatient setting.

Check out more stories featuring the great work of our nurses in the 2021 Nursing Annual Report (pdf).